Giovanni Sanna migrated to Australia in 1967, lived in the Illawarra and worked for most of his life for the Italian power transmission giant Electric Power Transmission (EPT). He never married and a few days ago he passed away alone in a Wollongong Hospital.

Before dying, he asked for a representative of the Italian Social Welfare Organisation of Wollongong (ITSOWEL), to visit him in hospital. The organisation’s president, Giovanna Cardamone did so, but by the time she saw Giovanni, he was delirious and near the end of his life.

“We will always be together. We will always be together and one day we will get married,” he repeated at the end of his life, Cardamone tells SBS Italian.

“I will never forget those words,” says an emotional Cardamone. “He was dying alone. But he was calling for someone, a distant love lost in time with whom he now wanted to be with forever.”

After his death, uncertainty surrounded the kind of burial Giovanni would receive. The thought of him “disappearing forgotten in a hole in the ground” was too much for Cardamone to contemplate and she decided take the funeral arrangements into ITSOWEL’s hands.

“Giovanni was one of us,” she says. “He deserved a dignified burial and a final resting place among Italian migrants. Now passers-by will read his name and lay a flower on his grave.”

Source: Courtesy of It.So.Wel.

Piecing together Giovanni’s story

Very little is known of Giovanni Sanna.

He migrated in 1967, the year when a total of 135,019 permanent settlers came to Australia in search of a better future in a distant land.

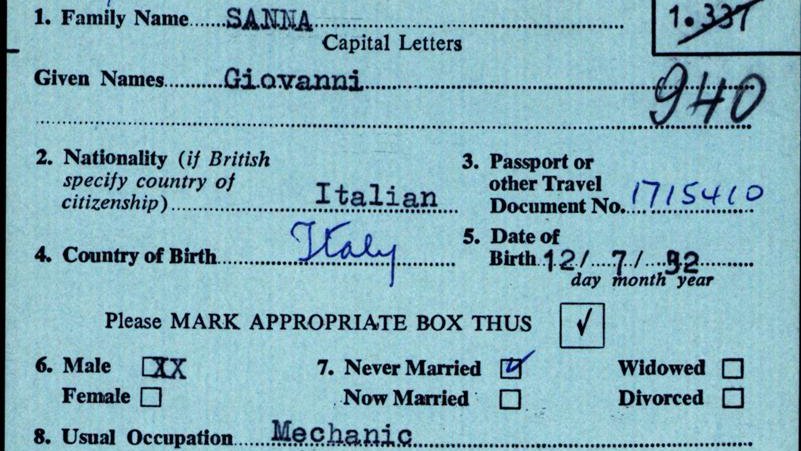

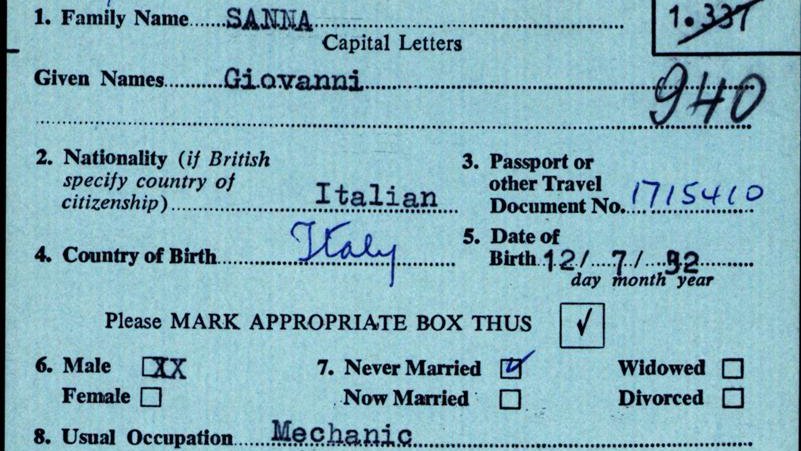

He was born in the Sardinian country town of Solarussa, a small town with less than 3,000 people. He had migrated first to Germany where he worked for many years in Stuttgart, probably in the car manufacturing industry, as his ‘incoming passenger card’ stated he was a mechanic by trade. Audi, BMW, Mercedes-Benz, Porsche, and Volkswagen all have factories in this town.

Giovanni was issued with his new passport by the local Italian Consulate and on 10 July 1967, two days before his 35th birthday, the Australian Embassy Migration Office in the German city of Cologne issued him with an Australian permanent visa under the Special Passage Assistance Programme.

He arrived in Fremantle on 15 September 1967 and moved to Sydney where he found work with EPT, an Italian company that built power lines across Australia. EPT had offices in every major Australian city and employed, at its peak, over two thousand workers, mainly Italians. After that, little more is known of his life.

After that, little more is known of his life.

Source: Courtesy of Matthew Quomi

A symptom of wider isolation

“I wonder how many people like Giovanni live and die in isolation in Australia,” says Giovanna Cardamone.

According to a VicHealth report, loneliness is increasingly common and can strike even if we have lots of friends or a big social network, affecting 80 per cent of Australians under 18 and 40 per cent over 65.

While it remains an emerging area of social research, it is concerning that despite our hyper-connected world, loneliness is increasing and having a serious impact on health and mental wellbeing, even increasing the risk of certain chronic conditions.

Loneliness and isolation are felt in the Illawarra region, where Giovanni Sanna lived. According to the 2016 census, Italians are the top ethnicity of overseas-born persons over 65 years residing in Wollongong, Shellharbour and Kiama.

“Within the Italian community rates of isolation, where people live alone due to the death of a spouse, are quite high”, says Cardamone.

Contrary to what is often an anonymous death for many Australians like him, ITSOWEL was able to give Giovanni Sanna a dignified burial. His grave is located within the Italian section of Wollongong’s cemetery for anyone to visit.

If not for ITSOWEL’s intervention, like most destitute people who die in isolation and without someone claiming their remains, Giovanni would have been cremated in the presence of a Public Health officer. The Area Health Service would have footed the bill and his ashes dispersed. Cremation is NSW Health Service’s preferred method used in cases such as this.

Combating loneliness

Efforts are made to locate and assist isolated people in Australia, in particular by the Red Cross.

New Red Cross data reveals that in 2018, volunteers made over 1.1 million calls to elderly and isolated Australians in need of a friendly chat to ensure they are safe and well.

Kerry McGrath, Director Community Programs at the Red Cross says their telephone service remains popular, “particularly among some of the older members of our community who enjoy an old fashioned conversation to a digital check-in.”

“Nearly 50 years ago, the service was established in response to stories of older people being found deceased and alone, and it has indeed filled a vital gap, and now our services responding to community isolation grow each year.

“We’re finding increasingly people want more than a welfare check and instead they prefer a longer chat and ultimately want human connection, which can be the difference between just existing and living,” she says.

At 89 years of age, one of Red Cross’s longest standing clients Nina has been receiving daily calls since turning 80. She says she values the sense of safety and comfort the service gives her.

“Living alone, Red Cross is my comfort blanket. I wake up and I know I’m going to have a little chat at 7am on the dot, like an alarm clock, and it makes me feel a little better about the day.

“I look forward to my calls and having someone to talk to. They have been my lifeline for a long time and you need that when you get older,” she says.

If you or someone you know needs companionship visit the Red Cross , for more information.